As someone who reviews tech products for a living, I have an entirely justified hatred for fake reviews. And fake reviews are an increasingly serious problem as they imbue product listings with unearned trust, tricking consumers and gaming search results.

The US Federal Trade Commission is preparing to bring the hammer down on fake and otherwise less-than-100-percent-honest reviews, on big stores like Amazon, social media, and even self-hosted online stores run by companies for their own products.

The FTC has now finalized its federal rules banning fake reviews online, with the Commission voting unanimously to adopt the standards it’s been working on for almost two years. It’ll officially go into effect, with regulatory power in the US, sixty days after it’s published in the Federal Register. That should make it active sometime later this year.

You can read the full text in the FTC’s announcement, but here are some of the notable updated rules, summarized by PCWorld:

No reviews or testimonials from people who don’t exist. That means companies can’t invent user profiles or mass-create reviews. The FTC is specifically disallowing AI-generated reviews of any kind, including those that use AI to impersonate real people and/or celebrities.

No buying reviews of any kind, positive or negative. “Buying” in this context includes any kind of compensation, including straight payments, “rebates” after you leave a review, and discounts on future purchases.

No reviews from company insiders. You can’t leave a review for a product — whether on your own website or a general online store — if you work for the company that sells the product or have some other financial relationship with them, like being a contractor. The FTC is also putting “requirements” on reviews solicited from family members, though what exactly those stipulations are weren’t spelled out in the press release. I’m guessing there will be some kind of disclosure clause.

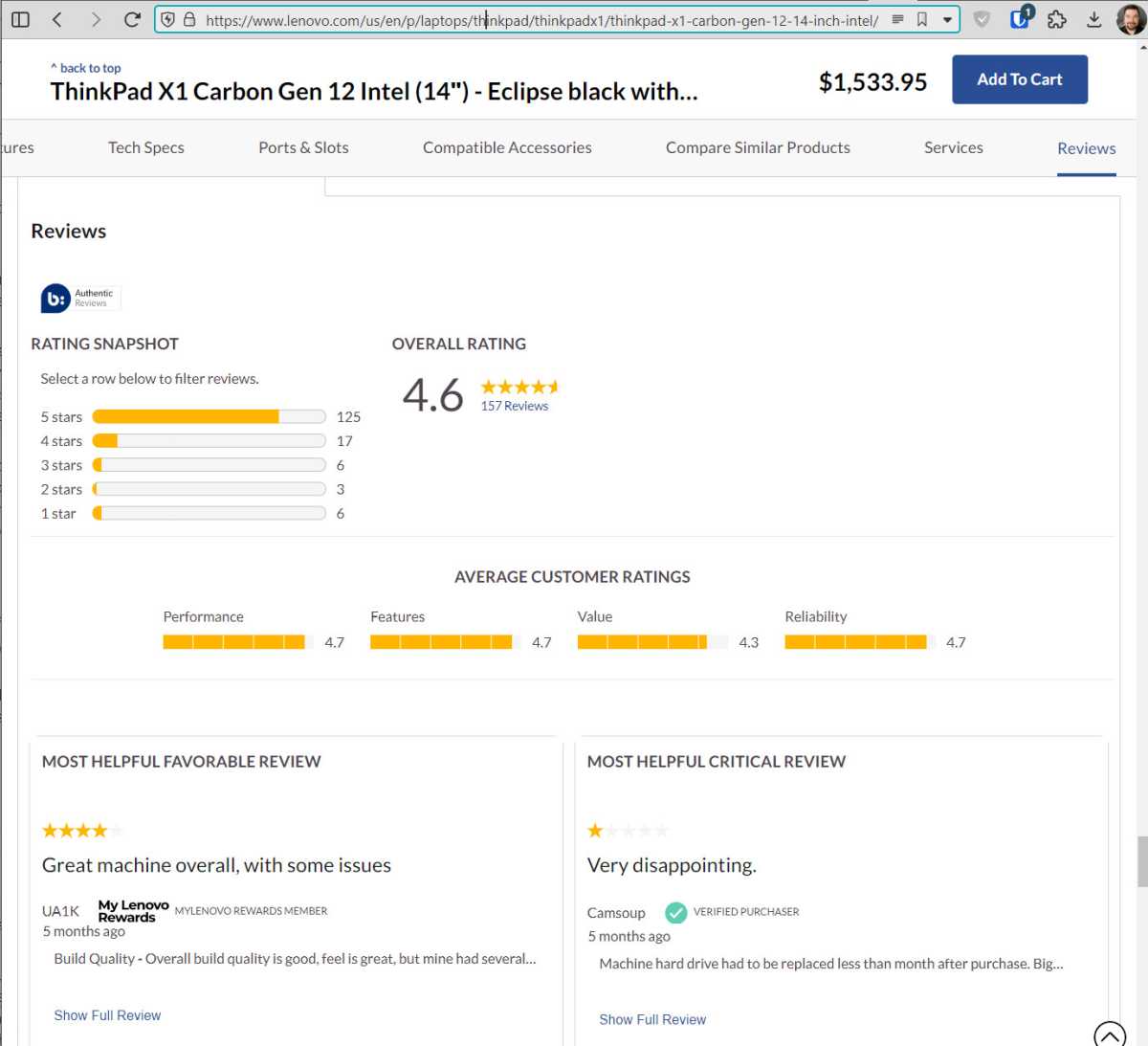

Lenovo

No fake review sites. Companies can still host reviews on their own pages (the kind you see on pretty much any promo site that doubles as its own store, like Lenovo’s above), but they can’t host review sites that fail to disclose that they’re owned by the company that’s selling the products in the review. For example, Purple couldn’t throw up a site like “BestMattressReviewsEva.com” that only gives Editors’ Choice awards to Purple mattresses and one stars to everything else. Or, at least, it would have to tell people that it’s doing so.

No review suppression. Companies can’t try to get negative reviews removed with “unfounded or groundless legal threats, physical threats, intimidation, or certain false public accusations.” That story you hear every month or so about some store trying to sue a customer for leaving a bad Yelp review? It will officially get the FTC’s attention now.

No buying or selling fake followers or fake views. The final rule specifically covers services that juice social media influence. It’ll be a federal violation to buy or sell social media followers, likes, or views that don’t correspond to real people. Anyone using “a bot or a hijacked account” is right out. The FTC says the rule specifically covers both sellers and buyers, if the latter “knew or should have known” they were buying fake influence.

The FTC has made rules covering reviews and advertising on the web and social media before, and that’s why influencers have to tell you when they’ve been provided with a product for free or when a video is sponsored. (It’s also why sites like PCWorld disclose when we show affiliate revenue links. You can spot it at the top of this page.)

But this push seems specifically aimed at reducing the flood of fake reviews and other less-than-genuine means of promotion. Each infraction will carry a maximum fine of over $50,000.

All of this is great for consumers… but there are limitations on how the FTC can actually enforce these rules. First, it’s US-only, so it only applies to companies doing business in the States. Technically, that includes places like Temu or AliExpress that sell to American residents, but actually enforcing these rules on anyone outside of the US is almost impossible. Stores like Amazon, Walmart, and Newegg will be motivated to enforce these rules on third-party sellers just about everywhere, but unless the sellers have actual assets in the US, they can thumb their noses at the FTC and other regulatory agencies and just move to another marketplace.

Second, the FTC is a regulatory agency, which means these rules are not laws passed by Congress. Companies like Amazon and Walmart can sue to challenge their validity and get them declared null by the courts — and right now, the federal court system leans heavily against regulatory power and in favor of corporations, recently gutting the federal government’s ability to enforce the rules its agencies put in place.