By now you probably know that your web activity is tracked at pretty much every step. Things like your IP address, a number associated with your connection to your internet service provider, and cookies, tiny files collected by your web browser, can identify you to websites, advertisers, and anyone who’s interested enough in your data to pay for it. But there are far more complex methods of tracking users on the open internet—ways that can get past even blocked cookies or an IP address masked with a VPN.

This collection of varied data to groups of users, and sometimes even a single user, is called a digital fingerprint. With a wide enough net cast to collect data through information gathered via websites and advertising, it’s possible to get a startlingly accurate picture of what a specific user is doing online, sometimes down to a near-complete history of their web usage.

Check out these 10 tricks to use Google Search more efficiently.

What a digital fingerprint isn’t

Despite the allusion to something you might see on a TV show about cops and investigators, a digital fingerprint isn’t a single file or point of data. Unlike a tracking cookie or an IP address, it’s a wide and varied set of information variables collected from your devices (smartphones, laptops and desktops, even things like smart TVs or appliances) as you use the internet. Combining all of this data together can track a single user and collect a log of their activity.

So, the bad news is there’s no magic pill or a single method of blocking a site or an advertiser from collecting all of this data. You can’t just turn on Incognito Mode and assume someone can’t get to your information. It means that if you want to keep from being monitored, you need to take a systemic approach to protecting your information and your activity. That goes for every device you’re using, whenever you’re using it.

What information is in a digital fingerprint?

What kind of data is being collected? A huge variety, some of which you may never have even imagined was being recorded. Obvious things like the type of web browser and operating system you’re using are some of the first steps, but with modern web technology, sites can gather data such as which browser extensions you have installed (like ad blockers or password managers), which programs or apps are installed on your device, the language your system is set to, or even the specific fonts you have installed.

Here’s a long, but by no means definitive, list of the different kinds of data that can be combined to form a digital fingerprint:

- Your estimated location, gathered from data like IP address, country reporting and your device’s time zone setting

- Your device’s type, manufacturer, operating system, and even the operating system version number

- Your web browser (reported by its user agent), browser version number, and settings like “Do not track” and default language

- Your browser’s installed plugins and extensions, like a PDF viewer or ad blocker

- Your device’s display information, including resolution, size, and even the available display dedicated to the web page itself

- Your device’s hardware permissions granted to the browser, like camera control, microphone, or accelerometer

- Your device’s basic hardware information, like battery level or available RAM

- Your installed video and audio formats for available media playback

- Your default keyboard layout, and whether you’re using a touchscreen or not

- Your installed fonts

- Complex browser information including HTTP headers, available APIs, CSS info, and JavaScript objects

Some tracking systems can get even more complex. For example, an embedded bit of script can query your device’s CPU to perform a quick cryptographic function, something it does in less than a second all the time. But by measuring how fast your gadget does the math, and comparing it to all the other devices performing the same test, it can get a benchmark of your processor and guess what type and model it is.

I should point out that there’s a reason that all this information is shared in the first place, and it’s typically harmless. For example, modern websites need to know your screen size and resolution in order to show you text you can read easily, and format it to fit on your screen so it doesn’t cover other elements of the page. But advertisers and other actors have found ingenious ways to collect and combine this data into incredibly complex tracking systems that don’t need old-fashioned cookies or IP numbers.

What can someone do with my digital fingerprint info?

Because modern devices are so complex, and modern always-online users tend to use their computers and gadgets so differently, it’s easy to combine all of these data points and narrow them down into small groups of users. In fact, if you’ve been using your phone or computer for more than a week or so and you haven’t taken specific steps to mask yourself, your digital fingerprint is probably unique—a collection of data so complex and specific that it points right to you, and only you.

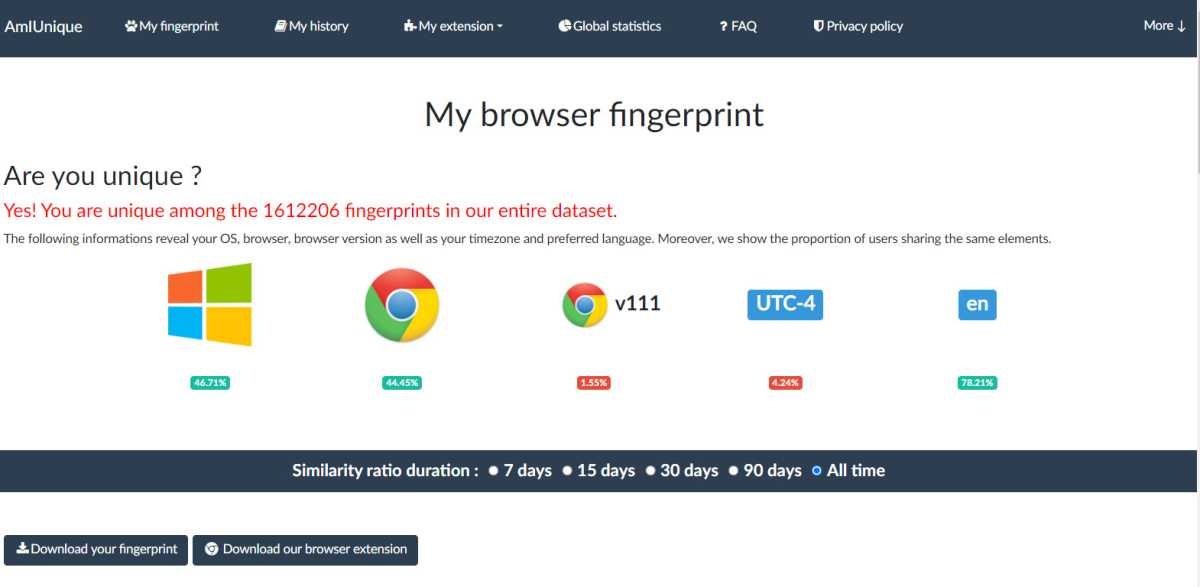

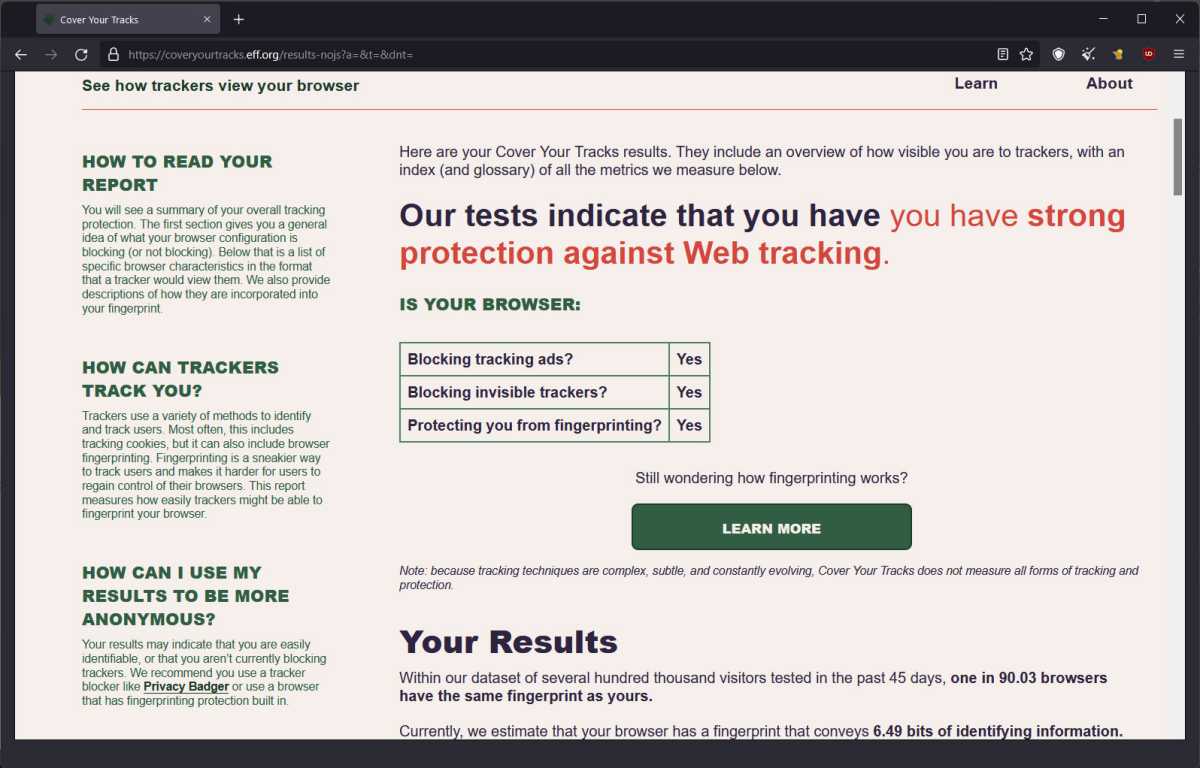

You can test this out with a service like AmIUnique.org or the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Cover Your Tracks tool. Unsurprisingly, both of these tools determined that my desktop computer is leaving a completely unique digital fingerprint among more than a quarter million surveyed results. It’s possible, and even pretty likely, that an advertiser can pinpoint my unique user profile among all the web traffic on the planet.

amiunique.org

That doesn’t mean that my digital fingerprint tells specific things about me, personally. It can’t know my age, nationality, race, sex, home address, phone number, etc—at least, not without connecting to some other database of stored information. But what it CAN do is track the websites I visit and what I do there.

That’s because websites and advertisers pass digital fingerprints around like trading cards. With a wide enough network collecting from websites and ads, especially the most commonly-visited sites like Google, Amazon, Facebook, YouTube, etc, you can build a nearly-complete record of what specific users are doing on the web. And by extension, you can build a profile of what they’re interested in…and what they might want to buy.

Yup, this all comes back to advertising, the backbone of the modern internet. (Feel free to click on a few of the ads you see on this page, by the way, they keep food on my table.) Now, it’s possible for governments, law enforcement agencies, hackers, and other scary people to track individuals using the same techniques. But unless you’re incredibly wealthy, someone highly placed in government or industry, or you’re on the run from the law, odds are pretty good you won’t be individually targeted using these techniques. It’s all about the ads, baby.

However, that advertising data can be connected to your personal information, at least if you’re logged into any site that has that information available to it. That presents a more moderate danger for things like identity theft or more elaborate attempts at harm, like phishing or pig butchering. Again, you’re more likely to be targeted by this if you’re wealthy or important.

How can I protect my digital fingerprint?

Because a digital fingerprint is made up of so many data points, it’s pretty hard to completely stop sites and advertisers from tracking you with it. Basics like spoofing your location with a VPN and blocking cookies just won’t cut it, though they do make it a lot harder for the tracker to narrow you down to a specific web user.

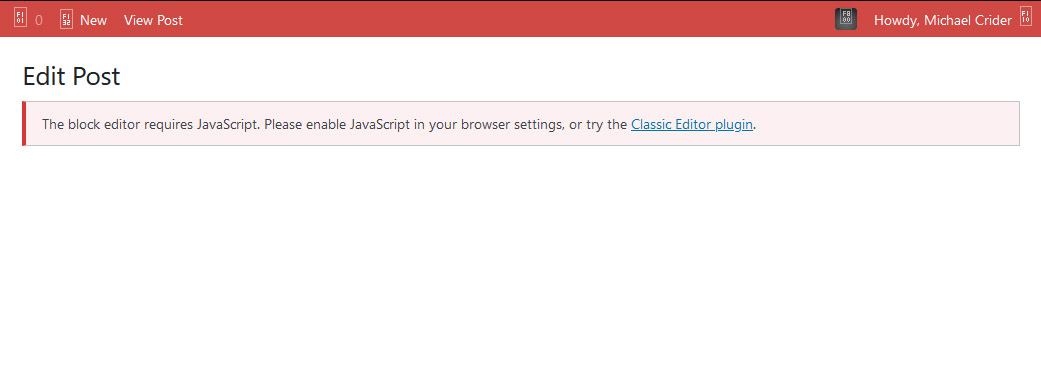

Blocking JavaScript with a tool like NoScript will restrict a lot of the data points being collected. But just like completely blocking cookies, that can make a lot of websites simply not work, especially more complex web services and tools. Using an ad blocker will also stop some, but not all, fingerprint data collection.

Setting Mullvad to super-safe mode lets me pass the EFF fingerprinting test, but…

Michael Crider/IDG

Some browsers have systems that try to limit the amount of data accessible for fingerprinting—Firefox blocks at least some of it, and more privacy-focused browsers like Tor, Brave, Mullvad, and DuckDuckGo either block the data or submit generic, non-specific information so fingerprinting becomes more difficult.

Michael Crider/IDG

But they aren’t perfect. For example, the AmIUnique and EFF tools I mentioned earlier said switching from Chrome to Mullvad made tracking harder, but my desktop PC still gave off a unique user footprint based on my hardware and software. I had to completely disable JavaScript in the settings to pass the tests. But doing so makes YouTube show nothing but grey boxes, and the WordPress interface I use to write articles for PCWorld relies on JavaScript, so this high-security mode isn’t really a feasible solution for me.

A difficult compromise

Digital fingerprinting has become a commonplace and ubiquitous practice for web advertising. So common, in fact, that it’s nearly impossible to use the internet without giving at least some data away, which can be used to create a profile for you and your activity. You can take steps to lower the amount of information collected, but engaging with any sort of complex web service (like an online shop or social network) means sharing at least some data that can be tracked.

The danger in a digital fingerprint isn’t immediate—there’s very little risk to targeted advertising, aside from its tendency to be annoying. The potential for mischief occurs when that data is combined with more personal information. And keeping your personal information safe goes back to more basic, practical security measures: keeping as little of that data in as few hands as possible.

Unfortunately, there’s no practical way to engage with the modern internet and leave zero fingerprints on your activity. The best you can do is make it a little harder for sites and advertisers to pin you down specifically.